The following article might be quite helpful for those wanting to understand the debate about the current account deficit in Australia.

Balance of power

TIM COLEBATCH

THE AGE

October 24, 2009

http://www.theage.com.au/business/balance-of-power-20091023-hdgu.html

IN THE wake of the global financial crisis, a crucial question confronting policymakers is why Australia seems to have got away with so little damage?

Was it a lucky escape, which should be a wake-up call for us to tackle our persistent current account deficit before it brings us down? Or was it, rather, evidence that the quality of our economic policies has made us invulnerable to the shocks dealt out by global financial markets?

This week, two of the economists Kevin Rudd listens to most carefully delivered sharply different readings of what has been dubbed "Australian exceptionalism", and its implications for the current account balance.

In one corner is Ross Garnaut, one of Australia's most influential economists since the 1980s, as economic adviser to then prime minister Bob Hawke, author of the 1989 report that led to the virtual demolition of the tariff wall, and more recently, the man Rudd commissioned to draft his policy on climate change — albeit, a draft he then rejected as too rigorous.

Garnaut, of course, also has a considerable sideline in corporate Australia, as long-time chairman of Lihir Gold and former chairman of what we now call Bankwest. Add in his time as ambassador to Beijing, where his staff included a young Mandarin-speaking workaholic who went on to achieve great things, and he brings an unusual range of experience to bear.

In the other corner is Ken Henry, secretary of Treasury since 2001, Rudd's main adviser on the Government's fiscal stimulus package, and a man now bearing a very heavy workload as chairman of its tax policy review at the same time as running a Treasury that now finds its work constantly in the spotlights of a bitter political debate.

On most issues, Garnaut and Henry see eye to eye. Both are mainstream economic liberals who believe that free markets are a powerful force for good. But both temper their faith in markets with a strong social and environmental conscience. They look to the long term, share a global perspective — and are men of subtle minds.

Yet now they are in sharp conflict over the question of whether Australia can afford to go on running the most persistently large current account deficit in the Western world: a deficit that has now averaged 4 to 4.5 per cent of our gross domestic product for the past 30 years, and driven our net foreign debt from $8 billion to $633 billion, or 53 per cent of our GDP.

It is a concern to Garnaut. With co-author David Llewellyn-Smith, he has just published an absorbing account of the crisis, The Great Crash of 2008 (MUP, $24.99), which is rich in reflections on its implications for global power relationships, for the future development of the financial system, and for key countries, not least Australia.

Garnaut sees the crisis as vindicating his warnings during recent years about "the great complacency" in Australian policymaking: the belief that the current account deficit and the associated build-up of foreign debt don't matter, but simply reflect the confidence with which foreign investors see us.

Australia's growth in recent years, he argues, has been unsustainable, because so much has been funded by increasing foreign debt — and you can't increase foreign debt forever. "Australians," he says, "were the spendthrifts of the commodities boom".

"If expenditure, both government and private, is allowed to expand too much when commodity prices are exceptionally high, there will be dreadful problems when it becomes necessary to adjust to lower living standards as prices fall to more normal levels.

"Australia has two strikes against it: its huge current account deficits before the crisis, and the deterioration in its terms of trade. They mean that Australia will have to reduce average consumption levels more than most countries if it is to restore full employment on a sustainable basis."

Henry strongly disagrees. In an unusually passionate speech in Brisbane on Thursday, the Treasury chief voiced strong confidence in Australia's economic future, along with equally strong fears about what it might mean for our environmental future, and for our wildlife, if Australia adds another 13 million people by 2049, as Treasury now projects.

Without naming Garnaut but clearly targeting his critique, Henry argued that Australia faced "a set of structural changes more profound than anything in its history": the ageing of its population, tackling global warming and adapting to it, the spread of the IT and communications revolution to the delivery of services — and the rapid growth of China and India, and their demand for Australian minerals.

"China and India are only in the early stages of catching up with the living standards of the developed world, and this process could have a very long way to run," Henry declared. "We should get used to the idea that we could have structurally higher terms of trade for quite some time — possibly for several decades."

We should also get used to the fact that Australia will keep borrowing and running current account deficits far into the future, Henry said. All the big changes we face will require higher investment. And our population is too small to be able to adequately fund "an abundance of investment opportunities".

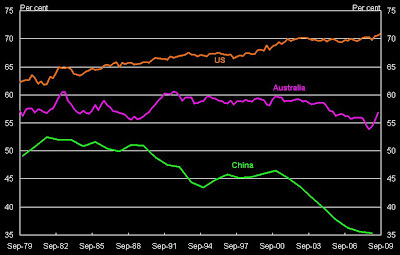

"Australia's sustained high current account deficits reflect high national investment rather than low national saving," Henry declared, flashing a graph showing the national savings rate soaring between 1990 and 2008. "And national investment levels could remain elevated for several decades."

Let's pause for a word of explanation. Current account deficits can be viewed on two planes. The deficit measures the gap between what you sell the world and what you buy from it (the trade deficit), plus the gap between what you pay to foreign investors here and what you earn from your own foreign investments overseas.

For Australia, both gaps are substantial. Over the past decade, our trade deficit has averaged 1.3 per cent of GDP, or $16 billion a year in today's money. Since 1980, Australia has run 25 annual trade deficits and only four surpluses — in the slumps of 1991-92, 2000-02, and 2008-09. Our income deficit has averaged 3.4 per cent rising, as mining profits and interest bills on the foreign debt have swollen.

But in analytical terms, the deficit can also be seen as the gap between Australia's savings and investment — which is the way Treasury prefers to view it. Since mining is capital-intensive, and our population is growing rapidly, Australia invests more than other Western countries. But despite the spin in Henry's speech, we are mediocre savers, consistently in the bottom half of the OECD in national savings to GDP, and in the bottom third for household savings.

(His graph used one of the oldest tricks of speakers flashing graphs: start your graph in the bust, and end it in the boom. Had his graph begun in 1987 instead of 1990, and ended in 2009 rather than 2008, it would have looked very different. Even at its peak in 2008, Australia's national savings rate was less than 20 years earlier, and it has plunged in 2009.)

Whichever way you prefer to view it, the solutions are the same. There are four ways to reduce the current account deficit. Export more. Import less. Save more. Or invest less.

Garnaut, a mining industry veteran, sees the high prices of recent years more as a transient phase, in which miners worldwide were caught unawares by China's rapid growth in demand. He also argues that China and India are going through a growth phase that is particularly resource-intensive.

Back in 2005-06, he argued in vain for the Howard government to save the windfall revenues from higher commodity prices, rather than handing them back in tax cuts and new spending. His book does not expand on this, but one option, advocated recently by Saul Eslake of the Grattan Institute, is to establish a sovereign wealth fund where temporary surges in company tax revenue could be stored for use in harder times.

Henry denies that policymakers have been complacent about the deficit. He argues that compulsory superannuation and a tradition of budget surpluses were established to lift saving rates and make Australia "able to sustain a sizeable current account deficit". His tax review is also expected to propose new tax breaks for savings, especially in the banks.

But can we sustain deficits of this size? No one can live indefinitely by borrowing. As your debts rise, so does the cost of servicing them. Henry's deputy, David Gruen, has estimated that Australia's debt-GDP ratio could be stabilised if the trade balance shifts by about 2 percentage points of GDP, from consistent deficit to consistent surplus. But there is no sign of that.

Henry's speech dismisses fears that one day financial markets might decline to roll over Australian debt, leaving borrowers stranded. "It would be difficult, I suggest, to construct a more demanding stress test of this vulnerability than that posed by the global financial crisis," he said. "The fact of our having passed that test provides grounds for some confidence, though certainly not complacency, in the strength of our policy frameworks and decision-making."

Yet as Garnaut points out in the book, it was precisely the refusal of foreign market to roll over bank debt in the panic of last October that led the Australian Government to guarantee the banks' wholesale borrowings. "Banks had become heavily reliant on foreign borrowing and suddenly they were unable to borrow abroad," he says. Had the Government not given the guarantee they sought, Australia would have faced an "enormously disruptive and costly" recession.

Was Henry's comment just a slip by an overworked public servant? Or did it imply that from now on, Australian banks' borrowings will carry an implied government guarantee, to be called on whenever needed?

As shadow trade minister in 2005-06, Rudd took up Garnaut's critique, advocating a higher priority for exports. Then as mineral prices surged and a trade surplus emerged, the issue faded from his priorities. But with export prices down 32 per cent this year, and trade now back in deficit by more than $1.5 billion a month, the current account deficit is back to haunt us.