I've long realised that one should not take many 'news' story on housing too seriously. A lot of them involve unashamed real estate industry spruking with either spokespersons for the industry putting them together or lazy journalists taking their line as fact.

I think there are just too many variables to be absolutely sure about where property prices will go in the next year, let alone the next 3, 5 or 10 years. But at the moment things look increasingly sour for property prices.

The most immediate variables are related to housing supply and housing demand. On the supply side: how much new housing is being supplied, do government regulations make it easy to build new houses and so on. On the demand side population growth and the availability of credit are vital factors, but population growth is more complex than many seem to realise.

Basic things such as the amount of people per dwelling is a vital but often forgotten factor.

When things get tougher economically, people in large houses might take on a border or older children might go back to live with their parents. So a rising population might not mean a proportional increase in the demand for housing. One of the big factors behind the property sprukers is the view that immigration will keep the housing market buoyant, but let's be realistic about newly arrived immigrants they are likely to have a higher occupation rate of housing units than other sectors of the population (at least initially and are likely to be renters of low cost properties).

Economy-wide variables are vital as well, starting with overall economic growth and extending to credit expansion and the level indebtedness. Some times the linkages can be difficult to fathom for many punters. Australian property prices will no doubt be linked to Chinese economic growth over the medium term. If Chinese growth falters, it will reduce prices and demand for Australian exports, which will in turn have a negative effect on Australian GDP and especially income. One of the key potential worries is the Chinese property bubble and what its eventual bursting will mean for Chinese growth.

Also vital to understand the housing market is the fact that different sectors of the market are likely to follow different trajectories. This is the case for coastal and inland markets and city and country ones. There are of course also key differences between cities and within cities (inner city, inner suburban, outer suburban, fringes etc).

As I've noted before one of the best writers on housing in Australia is Leith van Onselen who writes for Macro Business, which is a must read super blog for those seeking alternative economic views to the mainstream media.

In a recent post Leith pulls apart the sort of puff piece on property that media organisations love to put together. It should be required reading for all.

For an alternative view arguing that there is only a possibility of a slow decrease in price rather than any chance of bursting bubble see the very good economic commenator Jessica Irvine.

I think there are just too many variables to be absolutely sure about where property prices will go in the next year, let alone the next 3, 5 or 10 years. But at the moment things look increasingly sour for property prices.

The most immediate variables are related to housing supply and housing demand. On the supply side: how much new housing is being supplied, do government regulations make it easy to build new houses and so on. On the demand side population growth and the availability of credit are vital factors, but population growth is more complex than many seem to realise.

Basic things such as the amount of people per dwelling is a vital but often forgotten factor.

When things get tougher economically, people in large houses might take on a border or older children might go back to live with their parents. So a rising population might not mean a proportional increase in the demand for housing. One of the big factors behind the property sprukers is the view that immigration will keep the housing market buoyant, but let's be realistic about newly arrived immigrants they are likely to have a higher occupation rate of housing units than other sectors of the population (at least initially and are likely to be renters of low cost properties).

Economy-wide variables are vital as well, starting with overall economic growth and extending to credit expansion and the level indebtedness. Some times the linkages can be difficult to fathom for many punters. Australian property prices will no doubt be linked to Chinese economic growth over the medium term. If Chinese growth falters, it will reduce prices and demand for Australian exports, which will in turn have a negative effect on Australian GDP and especially income. One of the key potential worries is the Chinese property bubble and what its eventual bursting will mean for Chinese growth.

Also vital to understand the housing market is the fact that different sectors of the market are likely to follow different trajectories. This is the case for coastal and inland markets and city and country ones. There are of course also key differences between cities and within cities (inner city, inner suburban, outer suburban, fringes etc).

As I've noted before one of the best writers on housing in Australia is Leith van Onselen who writes for Macro Business, which is a must read super blog for those seeking alternative economic views to the mainstream media.

In a recent post Leith pulls apart the sort of puff piece on property that media organisations love to put together. It should be required reading for all.

Ponzi Dynamics

Leith van Onselen

An article in Friday’s Australian Financial Review (AFR) entitled “Getting a foot in the door” neatly highlighted the ponzi-like nature of the Australian housing market and the unsustainability of current housing values. Below are some extracts from the article along with some commentary of my own.

It took Lee Palmer two years of trying before he emerged from an auction, but in December he finally got his first house – all 40 square metres of it. The humble one-bedroom terrace in Darlinghurst, Sydney, set him back $641,000.Actually, once you add $24,900 in stamp duty and transfer fees and deduct the $7000 first home owners’ grant (FHOG), the purchase price rises to $658,900 for the “humble one bedroom terrace”… bargain!

It was a lot of money, but for Palmer it was worth it because he had a foot in the housing market. Now he is on the other side of the fence, where rising prices are in his favour…In his favour how exactly? Presumably Mr Palmer will want to upgrade to a larger home at some stage. And any rise in valuations across the Sydney property market will only make the upgrade more costly. Not only do stamp duties rise with property values but the monetary difference between his and the next level of home will also likely increase.

“It’s better than paying rent”, Palmer says. “Over the years I have looked at Sydney property it has never really dropped so [I thought] I might as well get in some time”.“It’s better than paying rent”. Really? A quick Realestate.com.au search of one bedroom rental properties in Darlinghurst turned up the following results:

So Mr Palmer could have rented a one bedroom studio for between $275 and $320 per week or a larger one bedroom place for between $395 and $500. If we assume that Mr Palmer’s home would rent for $500/week, renting would cost him $26,000 a year – representing a gross rental yield of only 4% on the purchase cost. If you compare this rental yield to the current discount variable mortgage rate of 7.1% and add on a bit extra for body corporate fees/rates, maintenance, etc, then the cost of renting in Darlinghurst is likely around one half the cost of owning.

Has Mr Palmer also not heard the phrase: “past performance is no indication of future performance”? Just because Sydney’s prices have risen in the past in no way means that they will continue to rise unabated in the future. One only has to look at housing markets overseas to see that housing values can fall. Beware false axioms.

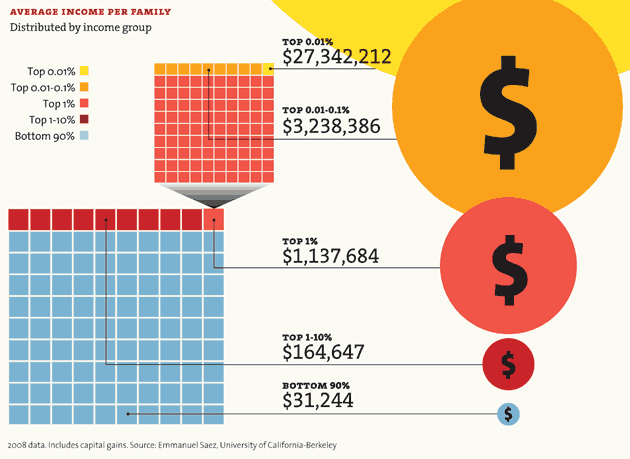

Property speculation has been a fountain of wealth for decades, and as baby boomers seek to retire and cash in, they are hoping young professionals like Palmer will take the baton. And many are going to great lengths to do just that.So the baby boomers, who comprise around a quarter of the population and own around half of the housing stock (see here and here), somehow expect that Generation Y (slightly larger in number) will have the ways and means to pay overinflated prices to the boomers as they “cash out”. Good luck with that.

Palmer leveraged his advantage as an employee at a major national bank, which enabled him to get a loan of 95% of the house’s value, without mortgage insurance, and with no fees. It allowed him to bid higher than others with the same finances.Seriously, if a skilled professional like Mr Palmer has to borrow 95% to purchase a “humble one bedroom terrace”, then how much more upside is left in the housing market? What’s next, young buyers borrowing 100%, 105%, 110%…? Oh well, I’m sure his bank employer is happy to have his business. What better way to tie someone to their job than enslave them in debt.

Others have had to be more resourceful. Like many first-time buyers Lauren Killmister had a little help from her parents. She saved a 10% deposit and they put in another 10%, enabling her to buy a one-bedroom apartment in Melbourne’s prestigious suburb of Hawthorn. She is living there now to qualify for the first-home owners’ grant, but will move back with her parents as soon as she has it in hand, and rent out her apartment. Maybe she will share house somewhere in a few years.Does this look like sustainable behaviour to you? Many young buyers are now having to turn to their parents for support and are gaming the FHOG in order to make ends meet. How exactly do the boomers expect Gen Y to “take the baton” when so many are unable to buy on their own?

Janusz Hooker of national franchise LJ Hooker calls the new wave of Gen Y buyers the “folio investors”, building up their portfolios from a young age. “We’ve got lots of cases of this… the older generation is seeing prices will be flat median term, selling out to cash in and the folio investors are jumping in. What they are doing is instead of buying their home and living in it, which they can’t afford, they are buying an investment property because of the tax benefits… They rent it out and hopefully get a large portion of their debt and interest repayments sorted through the rentals”.So Gen Y can’t afford to live in the homes themselves and are instead choosing to buy-to-let in the hope that the capital gains more than offset any income losses. Sounds like a ponzi scheme to me as the only way these Gen Y buyers can make a profit is if they offload their properties onto other buyers at a higher price (the ‘greater fool’ theory).

Mortgage adviser Catherine Lezer says it is common for parents to help them buy by putting some equity from their own home up as collateral… “Property goes up and rents go up, so the quicker people can get in the better”, she says.Ah yes, the old “property only goes up” claim. Once again, beware false axioms. Past performance is no indication of future performance.

Plenty of others call it a raw deal, paying such high prices for houses that previous generations bought for a much lower proportion of their income.Like the 21st speech where the speaker says some nice words after talking 10 minutes of smack about the birthday boy/girl, this is the token bit of the article where the reality is acknowledged. But don’t worry, it doesn’t take long for another industry representative to say everything’s ok:

But Justin Doobov [mortgage broker]… has been hearing the same complaints for years. “Five years ago they said it can’t go up any more, crazy prices, it’s too expensive, but then it went up further… People would prefer to pay their mortgage before they put food on their table”.Yeah right, I guess they are going to eat dirt then.

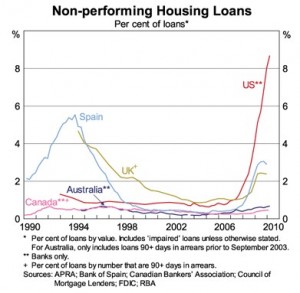

“Australia has such a low arrears rate”.So did Spain, the UK and the US prior to the bursting of their housing bubbles (see the below RBA chart). Ireland, too, had mortgage arrears below 1% before its housing market imploded. Arrears are a trailing indicator, not a predictive indicator.

“There is going to be huge migration and a lot of them are coming with money and they’re buying property. That’s just going to fuel more demand and push up prices”.That’s funny, I thought immigration was falling (see below RP data chart).

With arguments like those, what could possibly go wrong?

For an alternative view arguing that there is only a possibility of a slow decrease in price rather than any chance of bursting bubble see the very good economic commenator Jessica Irvine.