Who would have thought cutting government spending in the middle of a slump would lead to lower growth? Anyone with half a brain that's who. I'm not talking about Australia here, but Britain. However, Britain provides an example of what could have happened in Australia if simple-minded austerity politics had operated as per the Coalition's critique of Labor's fiscal expansion during 2008-09. Certainly the fact that the Chinese didn't believe in austerity helped our cause as well.

While China certainly came to the rescue after the slump, according to

Treasury (see

this also), it is the fiscal expansion that kept Australia out of recession during 2009. Despite revisionist views that it was all about China, it was fiscal expansion that helped Australia to avoid a downturn in business and consumer confidence during 2008 and 2009, which may have led to a negative spiral of increasing unemployment and declining consumption.

Here as a reminder is how bad things were late last decade on a global scale

As

Steve Morling and Tony McDonald point out:

As stark as these annual growth figures are, they disguise the speed and extent of the decline in the second half of 2008. In through-the-year terms, world growth fell from 3.8 per cent in the June quarter 2008 to -2.8per cent in the March quarter 2009, a 6.6 percentage point turnaround. The extent of the slowdown over this period was quite similar in the advanced and emerging economies.

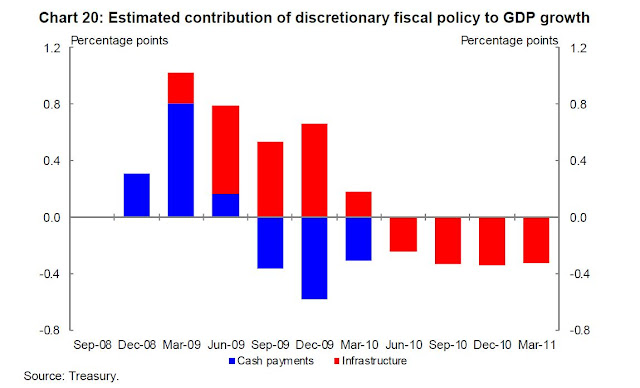

A couple of other charts from their paper make interesting viewing.

The first chart shows that the fiscal expansion, hit when it was needed most, during the second half of 2008 and first half of 2009.

If the global economy goes pear shaped in 2012-13, then the government should and probably will make the government contribution to growth help us avoid the severe downturn that will occur elsewhere. Still, what happens in China matters more and more, not just the direct impacts of Chinese demand on Australia but the indirect effects of Chinese demand for the goods and services of other Asian countries, which also helps us to keep growing. Even if Asia has decoupled from the rest of the world (which in the medium term I don't think it has), the countries of Asia have not decoupled from each other.

This second chart shows that the downturn badly affected China as well and our major trading partners in general. During this period of time, Australia was not being saved by China or the rest of Asia.

On a per capita basis Australia's growth performance was not as exemplary. Remember that GDP per capita is a much better measure of progress than aggregate GDP, which can be bolstered, as it has been throughout Australian history, by population increases.

Another interesting chart shows the differences between Australia's economic structure and the OECD average. In the 1980s these differences were seen as likely to lead to Australia falling down the rankings of of advanced economies. Now they are seen as a fundamental factor in our economic success. It is possible, if Australian policy-makers don't work to diversify the economy, that in 20 years time we might be making the same arguments about the Australian economy that were made in the 1980s.

Labor's determination, therefore, to produce a surplus sooner rather than later is not the same thing because of Australia's better and sustained recovery (so far) from the downturn on the back of Asian demand (remember the Asia story is much more than just China). The government was right to get the budget balance in order, while the sun's been shining. Indeed, they might have had a better shot at this if they'd raised taxes on mining profits sooner rather than later.

Wayne Swan and Treasury realise that if global growth falls off a cliff then they have room to manoeuvre to again support the economy through fiscal expansion (i.e. government spending).

While there may be too much focus on Europe's possible negative effects on Australia at the moment, it's important to remember that Europe as a whole accounts for about 40 per cent of global GDP. (The European Union itself is a larger economy than the United States).

The difficulty in the face of a return to a renewed global recession might be in ignoring those who believe that governments should be more like virtuous households - with a keen saving and protestant work ethic.

Instead they will have to make a case that increasing government spending will be a necessary move to avoid a downward economic spiral that could be caused by stupidly believing that austerity is a suitable policy during a slump. Expect the Coalition to go on about unsustainable public debt. Just make sure you realise that this is rubbish. The aim of government fiscal and monetary policy during a downturn should be to maintain aggregate demand. The Rudd government and the Reserve Bank did a good job during the last global recession, let's hope that they do an equally fine job during the coming downturn.

The major example of stupid austerity has been Britain, which has gone from bad to worse as far as growth is concerned.

Paul Krugman nicely captures the perverse reasoning in the UK of so-called "expansionary austerity", wherein advocates argued that cuts in government spending would encourage confidence in the business sector and lead to investment, jobs and finally consumption. Krugman begins by quoting UK PM, David Cameron:

“Those who argue that dealing with our deficit and promoting growth are somehow alternatives are wrong,” declared David Cameron, Britain’s prime minister. “You cannot put off the first in order to promote the second.”

But this is faith of the highest order, based on the same sort of logic as the

Laffer Curve.

How could the economy thrive when unemployment was already high, and government policies were directly reducing employment even further? Confidence! “I firmly believe,” declared Jean-Claude Trichet — at the time the president of the European Central Bank, and a strong advocate of the doctrine of expansionary austerity — “that in the current circumstances confidence-inspiring policies will foster and not hamper economic recovery, because confidence is the key factor today.”

Such invocations of the confidence fairy were never plausible; researchers at the International Monetary Fund and elsewhere quickly debunked the supposed evidence that spending cuts create jobs. Yet influential people on both sides of the Atlantic heaped praise on the prophets of austerity, Mr. Cameron in particular, because the doctrine of expansionary austerity dovetailed with their ideological agendas.

Instead what has happened has been - surprise, surprise - lower growth. According to a recent

National Institute of Economic and Social Research press

release:

output [in Britain] grew by 0.1 per cent in the three months ending in December after growth of 0.3 per cent in the three months ending in November. This implies the economy expanded by 1 per cent in 2011, half the rate of growth experienced in 2010 (2.1 per cent).

Krugman highlights an interesting graph from the NIESR (but doesn't show it) that reveals that in terms of growth Britain is doing worse than during the Great Depression.

Last week the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, a British think tank, released a startling chart comparing the current slump with past recessions and recoveries. It turns out that by one important measure — changes in real G.D.P. since the recession began — Britain is doing worse this time than it did during the Great Depression. Four years into the Depression, British G.D.P. had regained its previous peak; four years after the Great Recession began, Britain is nowhere close to regaining its lost ground.

Here's the

graph:

Given the rhetoric of the Conservatives one would think that Britain's public debt situation is unparalleled. In terms of

British history it is not even close to the high debt levels of the past.

The problem for the present and near-term is that low growth is not confined to Britain, which is still an important economy in the global scheme of things despite its long term

relative economic decline. Other still important economies are also doing poorly.

Italy is also doing worse than it did in the 1930s — and with Spain clearly headed for a double-dip recession, that makes three of Europe’s big five economies members of the worse-than club. Yes, there are some caveats and complications. But this nonetheless represents a stunning failure of policy.

And it’s a failure, in particular, of the austerity doctrine that has dominated elite policy discussion both in Europe and, to a large extent, in the United States for the past two years.

O.K., about those caveats: On one side, British unemployment was much higher in the 1930s than it is now, because the British economy was depressed — mainly thanks to an ill-advised return to the gold standard — even before the Depression struck. On the other side, Britain had a notably mild Depression compared with the United States.

Even so, surpassing the track record of the 1930s shouldn’t be a tough challenge. Haven’t we learned a lot about economic management over the last 80 years? Yes, we have — but in Britain and elsewhere, the policy elite decided to throw that hard-won knowledge out the window, and rely on ideologically convenient wishful thinking instead.

Krugman goes on to talk about the United States, whose policy-makers he believes need to be more focused on expansion, despite the high level of government debt. Those following the US debate know that many economic and political commentators believe that there needs to be austerity

à la Britain if the United States is going to break out of along period of low growth.

But this is madness, at least in the short-term. Krugman is thankful that the Obama Administration did not follow the expansionary austerity stupidity.

Which is not to say that all is well with U.S. policy. True, the federal government has avoided all-out austerity. But state and local governments, which must run more or less balanced budgets, have slashed spending and employment as federal aid runs out — and this has been a major drag on the overall economy. Without those spending cuts, we might already have been on the road to self-sustaining growth; as it is, recovery still hangs in the balance.

And we may get tipped in the wrong direction by Continental Europe, where austerity policies are having the same effect as in Britain, with many signs pointing to recession this year.

The infuriating thing about this tragedy is that it was completely unnecessary. Half a century ago, any economist — or for that matter any undergraduate who had read Paul Samuelson’s textbook “Economics” — could have told you that austerity in the face of depression was a very bad idea. But policy makers, pundits and, I’m sorry to say, many economists decided, largely for political reasons, to forget what they used to know. And millions of workers are paying the price for their willful amnesia.

Too many people think of an economy as just a big household. It's a good thing for families to increase their savings during a downturn - it's a little boring perhaps, but a good idea - because if times get even worse, i.e. if you lose your job or get fewer hours, then extra savings will perhaps help you and your family get through tough times.

This is not true, however, for an economy as a whole. The more people save the less they spend, leading to what Keynes called the

'paradox of thrift', wherein ‘virtuous’ efforts to reduce debt cause a decline in demand and a downturn in the economy.

Remember that GDP = private consumption + gross investment + government spending + (exports − imports). That is:

GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

Simple maths would tell you that if you reduce private consumption or government spending and don't get a corresponding increase in investment, then the end result will be an economic contraction.

The problem for Australia, as I

highlighted recently, is the end of the debt-fuelled growth model that spurred growth from the early 1990s til 2007. This is a major structural change for the Australian economy, although it might be better seen as the end of an earlier structural change that began with financial liberalisation and gathered pace as credit markets expanded over the 1990s and kept going until 2007 when the music stopped and not everyone found a chair.

As I outlined in that late 2011 post:

The growth of household debt as a percentage of disposable income grew rapidly over the 1990s and 2000s rising from:

48% in September 1990 to 156.7% in June 2007 to 150.8% in September 2011.

Debt for housing is 89.7 % of total household debt.

Investor housing debt is 29% of total household debt.

Interest payments as a percentage of disposable income reached a high of 13.4% in June 2008 to a low of 9.3% in June 2009 to 11.4% in September 2011. (see my article Structural Shenanigans for graphics).

So ... household debt remains at high levels and the inability to continue to grow debt even further undermines an important source of growth over the past 20 years.

Think about it.

The growth that occurred after the recovery of the 1990s recession was augmented, buttressed and sometimes driven by the expansion of household debt by around 100% of disposable income.

If we were to have the same favourable conditions over coming years this would mean that household debt as a percentage of disposable income would have to go to 250% of income.

While I've always been a keen user of credit cards, even I couldn't sustain the amount of debt repayments as a percentage of disposable income that this level of debt implies.

While households in aggregate have less room to move in terms of increasing GDP (the C part of our GDP equation), government in Australia (the G part of the equation) has much more room to move if things go badly in Europe, Asia and the United States.

We must hope that those successful communists in China keep managing their economy in such a way that benefits Australians. Over the short and medium-term it continues to be important that we debate the wisdom of increasing reliance on the mining sector and on China.