The Abbott government has repeatedly cut the foreign aid budget over recent years, causing much angst among the aid community. In 2015-16, Australia's aid budget will be a spartan $4.05 billion. The most recent cuts come on top of significant cuts made in the Mid–Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2014–15 (MYEFO) released on 15 December 2014. These cuts were made despite a reassurance from Foreign Minister Julie Bishop in January 2014 that "from 2014/15 the $5 billion aid budget will grow each year in line with the Consumer Price Index." According to Ravi Tomar

The Lowy Institute poll found that a majority were in favour of cuts, with only 19 per cent strongly against.

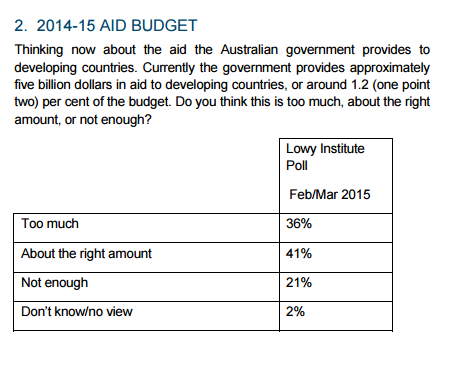

Over two-thirds of those polled thought that the current allocation of around $5 billion was too much, although a slightly greater number thought that this was about right.

In the Lowy polls, respondents are informed of the level of aid and then asked to comment, but a recent Essential poll shows that many Australians are misguided about the level of aid spending. Only about a quarter of those polled had any real idea of the level of Australian foreign aid.

There are two relevant statistics when considering the level of aid spending. The raw numbers are less revealing than figures relating spending to overall budget spending and gross national income (GNI).

The general picture of foreign aid in Australia is that the level of spending goes up when Labor is in power and down when the Coalition is in power. This trend has recently been accentuated by the Abbott government, which has cut spending to the lowest level for quite some time.

According to the Lowy Institute:

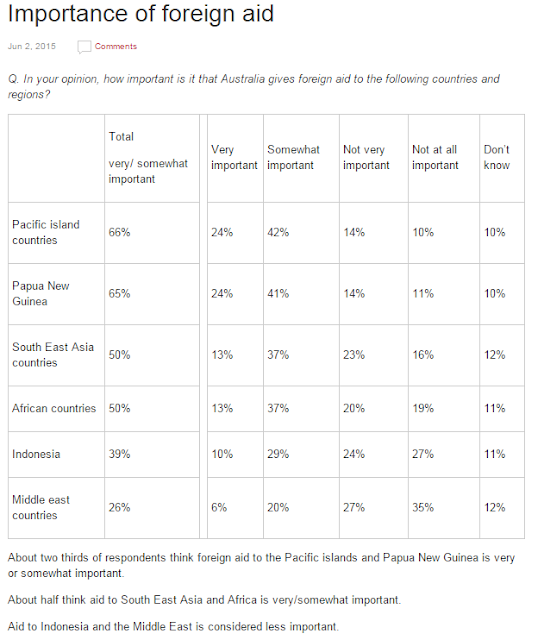

As far as aid priorities go, Pacific Island countries and Papua New Guinea are deemed to be the most worthy, with the Middle East the least worthy. In the eyes of many Australians, it is possible that the Middle East is more 'worthy' of our military spending.

These polls highlight some of the difficulties for those arguing for more aid spending by the Australian government. The perceptions is that Australia gives too much and that it goes to unworthy recipients.

The problem is that a lot of aid does get spent on administration and a lot does get siphoned off by corrupt elites. Education about current levels of aid and efforts to make aid more effective and less corrupt will help, but it is clear that many Australians have significant concerns about aid more generally. These concerns make it reasonably easy for Coalition governments to cut aid as a way to cut spending more generally. Aid recipients don't get a vote and make an easy target for critics.

In the last Budget the Coalition argued:

Foreign Minister Julie Bishop argues that the Coalition has developed a new aid paradigm focusing "on ways to drive economic growth in developing nations and create pathways out of poverty." She continues:

The commitment to keep growth in the aid budget tied to the CPI did not last very long. The Mid–Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2014–15 (MYEFO) released on 15 December 2014 stated that the Government would save $3.7 billion over three years from 2015–16: $1,000.0 million in 2015–16, $1,350.0 million in 2016–17 and $1,377.0 million in 2017–18.

In other words ODA would now be capped at around $4 billion and would decline in real terms in coming years, reaching an all-time ODA/GNI ratio low of 0.22 per cent in 2016–17.[3] If current budget forecasts are any guide, the ODA budget is in for a sustained period of decline in real terms.Despite the widespread criticism of the Abbott government's commitment to aid, a majority of Australians are not perturbed by the Abbott government's decisions to cut aid, according to recent polling. The general indifference to aid cuts means that the government faces few electoral pressures to increase its level of funding.

The Lowy Institute poll found that a majority were in favour of cuts, with only 19 per cent strongly against.

Over two-thirds of those polled thought that the current allocation of around $5 billion was too much, although a slightly greater number thought that this was about right.

In the Lowy polls, respondents are informed of the level of aid and then asked to comment, but a recent Essential poll shows that many Australians are misguided about the level of aid spending. Only about a quarter of those polled had any real idea of the level of Australian foreign aid.

There are two relevant statistics when considering the level of aid spending. The raw numbers are less revealing than figures relating spending to overall budget spending and gross national income (GNI).

The general picture of foreign aid in Australia is that the level of spending goes up when Labor is in power and down when the Coalition is in power. This trend has recently been accentuated by the Abbott government, which has cut spending to the lowest level for quite some time.

According to the Lowy Institute:

Australia's aid budget has now fallen to $4 billion, down from $5.6 billion in 2012-13.

According to calculations by the Development Policy Centre at ANU, the government’s budget cuts mark both the largest ever multi-year aid cuts (33 per cent) and largest ever single year cuts (20 per cent and $1 billion in 2015-16), that will see Australian aid will fall to 0.22 per cent of Gross National Income in 2016-17. Soon after coming to power in September 2013, the Abbott Government announced the integration of AusAID, Australia’s stand-alone aid agency with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade – to enable the closer alignment of the aid and diplomatic arms of Australia’s international policy agenda. ...

The 2015-16 Budget indicates how Australia will achieve the 20% cut. The decisions seem to have been made from a geographical and political viewpoint rather than through an assessment of the development effectiveness of each country and program

With the exception of Cambodia, Nepal and Timor-Leste, aid to countries in Asia was cut by 40%. The Pacific and Papua New Guinea were largely spared (only a 5% cut to PNG and 10% cut to Pacific Regional funding). Sub-Saharan Africa was slashed by 70%, and aid to the Middle East was cut by 43%. As a result, Papua New Guinea replaces Indonesia as the largest recipient of Australian aid, receiving $477.4 million in 2015-16.Of course if you think that aid spending is as high as 5 per cent of the Budget, then there's a good chance you'll think that aid spending is too high. It might be better for future polls to ask: "given that Australian aid is approximately 0.22 per cent of Gross National Income and less than 1 per cent of the Budget, do you think Australia spends too much, not enough etc." According to the Poll, nearly half could not give an estimate. But this did not stop respondents from suggesting Australia gives too much.

As far as aid priorities go, Pacific Island countries and Papua New Guinea are deemed to be the most worthy, with the Middle East the least worthy. In the eyes of many Australians, it is possible that the Middle East is more 'worthy' of our military spending.

These polls highlight some of the difficulties for those arguing for more aid spending by the Australian government. The perceptions is that Australia gives too much and that it goes to unworthy recipients.

The problem is that a lot of aid does get spent on administration and a lot does get siphoned off by corrupt elites. Education about current levels of aid and efforts to make aid more effective and less corrupt will help, but it is clear that many Australians have significant concerns about aid more generally. These concerns make it reasonably easy for Coalition governments to cut aid as a way to cut spending more generally. Aid recipients don't get a vote and make an easy target for critics.

In the last Budget the Coalition argued:

The Australian Government’s new development policy Australian aid: promoting prosperity, reducing poverty, enhancing stability is shaping the way we deliver our overseas development assistance. It focuses on two development outcomes: supporting private sector development and strengthening human development.

Investments will be focused on priority areas: ― infrastructure, trade facilitation and international competitiveness; ― agriculture, fisheries and water; ― effective governance through policies, institutions and functioning economies; ― education and health; ― building resilience through humanitarian assistance, disaster risk reduction and social protection; and ― gender equality and empowering women and girls.But the headline figures seem to imply that the Coalition doesn't really rate aid as a priority. Not all conservative governments have such an austere attitude to aid. The Conservative government in Britain has increased aid to over 0.7 per cent of GNI, a target that OECD countries committed to in 1970. According to the OECD:

In 1970, The 0.7% ODA/GNI target was first agreed and has been repeatedly re-endorsed at the highest level at international aid and development conferences:The Coalition's budget cuts are clearly seen in the graph of ODA/GNI since 1971-72.

- in 2005, the 15 countries that were members of the European Union by 2004 agreed to reach the target by 2015

- the 0.7% target served as a reference for 2005 political commitments to increase ODA from the EU, the G8 Gleneagles Summit and the UN World Summit

Foreign Minister Julie Bishop argues that the Coalition has developed a new aid paradigm focusing "on ways to drive economic growth in developing nations and create pathways out of poverty." She continues:

In recent years the world has changed and traditional approaches to aid are no longer good enough, and aid alone is no panacea for poverty.

The most effective and proven way to reduce poverty is to promote sustainable economic growth. Under the Coalition Government, Australia’s aid funding will go to creating jobs, boosting incomes and increasing economic security in our region.

Under this new policy, new aid investments will consider ways to engage the private sector and promote private sector growth. Aid for trade investments will be increased to 20 per cent of the aid budget by 2020.

The policy will focus on the Indo-Pacific region, with over 90 per cent of country and regional program funding spent in our neighbourhood, the Indo-Pacific, because this is where we can make the most difference.

The aid program will invest heavily in education and health, as well as disaster risk reduction and humanitarian crises. Improving education and health outcomes is essential to laying a foundation for economic development. $30 million each year will go toward researching ways to make the money we spend on health more effective and to promote medical breakthroughs.

I aim to focus on fewer, larger investments, to increase the impact and effectiveness of our aid.

Australia will continue to be one of the world’s most generous aid donors with a responsible, affordable and sustainable aid budget of over $5 billion a year.It all sounds good and fits with prevailing business oriented, market enhancing development, but regardless of whether one thinks this is the way forward for Australia's aid program, it is stretching things to argue that Australia is one of the world's most generous aid donors. To achieve this aim Australia would need to spend more than 0.22 per cent of GNI. Sweden is a generous aid donor, Australia is not, with the level of aid as a percentage of GNI below the DAC average.

Australia is a long way from the goal of 0.7 per cent of GNI. Indeed, it is a long way from the Rudd government's goal of Australian aid spending reaching 0.5 per cent of GNI. Like so many other issues of foreign policy, the public is often relatively uninformed and unsympathetic to the goals of the foreign policy establishment. Public education could help, but given its spending cuts, it is clear that the Abbott government shares with sections of the public some of its scorn for aid.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please be civil ...