Introduction

Australia is a country made up primarily of migrants and those descended from migrants. Since World War II over 7 million migrants have come to Australia and over a quarter of the population was born overseas. Like foreign investment, which has been equally essential for Australian prosperity, immigration is a contentious issue that polarises the Australian community.

It is also is an issue that produces strange bed fellows such as the belief by some on the right and the (environmental) left that Australian population growth needs to be limited or even reversed, which obviously means either restricting immigration or the birth rate. The differences between these two extremes lies in the desire or not for discriminatory immigration. Australians, it seems, don't want the

"big Australia" that then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd spruked in 2009. His successor, Julia Gillard,

abandoned such rhetoric and has put the population question to one side as she battles the opposition on the conundrum of asylum seekers.

To understand immigration we need to distinguish between flows - the yearly movement of people in and out of Australia and stocks - the cumulative results of these flows over time. We also need to distinguish between types of immigration divided between the Migration Program and the Humanitarian Program.

Australia's Overseas Born Population

The ABS has just released its

migration statistics, which put recent 'flow' figures into a 'stock' perspective.

While India is now the leading source of new migrants (

not including New Zealand - a fact that none of the news stories I read on the statistics noted) the statistics show that the UK remains the largest source of overseas born Australians.

According to the

ABS: "At 30 June 2011, 27% of the estimated resident population was born overseas (6.0 million people). This was an increase from ten years earlier at 23.1% (4.5 million people)."

The percentage of Australians born overseas has increased significantly since WWII, after declining precipitously after the 1890s.

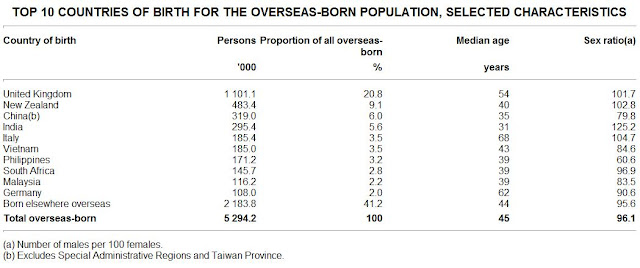

People born in the United Kingdom accounted for 5.3% of Australia's total population at 30 June 2011. This was followed by New Zealand (2.5%), China (1.8%), India (1.5%) and Vietnam and Italy (0.9% each).

The percentage born in the UK are in decline, however, falling from 5.8% in 2001 to 5.3% in 2011. New Zealanders, however, increased their share from 2% to 2.5%, China from 0.8% to 1.8% and India from 0.5% to 1.5%.

In terms of Australia's population growth, for the top 50 countries of birth at 30 June 2011, persons born in Nepal had the highest rate of increase between 2001 and 2011 with an average annual growth rate of 27%. However, this growth began from a small base of 2,800 persons at 30 June 2001. The second fastest increase over this period was in the number of persons born in Sudan (17.6% per year on average), followed by those born in India (12.7%), Bangladesh (11.9%) and Pakistan (10.2%).

Of the top 50 countries of birth, the number of persons born in Hungary decreased the most, with an average annual decrease of 1.4%, closely followed by both Italy and Poland, with an average annual decrease of 1.3% each. The next largest decreases were of persons born in Malta and Cyprus (0.8% each).

According to the

2011 Census: "over a quarter (26%) of Australia's population was born overseas and a further one fifth (20%) had at least one overseas-born parent ... the proportion of the overseas-born population originating from Europe has been in decline in recent years, from 52% in 2001 to 40% in 2011."

If we consider the makeup of the overseas born, then the UK accounts for over 20.8 per cent, followed by New Zealand with 9.1 per cent, China with 6.0 per cent and India with 5.6 per cent.

Ancestry

Ancestry is another important component in considering Australia's ethnic makeup, but is

not necessarily related to place of birth rather it provides an indication of cultural affinity.

According to the

ABS report on Cultural Diversity:

It gives insight into the cultural background of both the Australian-born and overseas-born populations when ancestry differs from country of birth. The 2011 Census asked respondents to provide a maximum of two ancestries with which they most closely identify. As an example, they were asked to consider the origins of their parents and grandparents.

Over 300 ancestries were separately identified in the 2011 Census. The most commonly reported were English (36%) and Australian (35%). A further six of the leading ten ancestries reflected the European heritage in Australia with the two remaining ancestries being Chinese (4%) and Indian (2%).

Just under a third (32%) of people who responded to the ancestry question reported two ancestries. Second generation Australians were the generation most likely to report a second ancestry (46%). This may be due to having a strong connection to Australia and also to a parent's country of birth. Third-plus generation Australians were less likely (36%) to report a second ancestry. As both the respondent and their parents were Australian-born, they may be less likely to have a connection to more than one country. The group least likely to report a second ancestry were first generation Australians (14%).

The vast majority of people who reported an Australian ancestry were born in Australia (98%). For most other ancestries, the majority of people were born either in Australia or the country associated with their ancestry. The European ancestries in the top 10 ancestry groups follow this pattern. For example, 83% of people who reported German ancestry were born in Australia and 10% were born in Germany. Only 7% were born in other countries. This pattern differed for the Asian countries in the top 10 ancestry groups. For example, for those who reported Chinese ancestry, 36% were born in China, 26% in Australia and 38% born in other countries. Of those who reported Indian ancestry, 61% were born in India, 20% in Australia and 19% born in other countries.

Data on the 'flow' of migration in recent years is covered by The Department of Immigration and Citizenship's

Migration Program Statistics.

Family related migration has accounted for between 31 and 35 per cent and skilled-related between 64 and 69 per cent.

According to the

2011-12 Migration Program Report India was the largest source of migrants, followed by China and the UK.

It is important to note that New Zealanders are not included in these figures.

Elsewhere DIAC states that New Zealanders have "been the major source country for settlers" since 2009 accounting for about 20 per cent in 2010-11.

The figures for 2010-11 were:

- New Zealand (20.2 percent)

- China (11.5 percent)

- United Kingdom (8.6 percent)

- India (8.3 percent)

The sub-continent region is now the largest source of migrants to Australia, replacing North Asia.

A Longer-Term Perspective

To put these recent statistics into historical perspective, according to

DIAC:

Since October 1945, more than 7.2 million people have migrated to Australia—750,000 of these people arrived under the Humanitarian Program. ...

About one million migrants arrived in each of the six decades following 1950:

•1.6 million between October 1945 and June 1960

•about 1.3 million in the 1960s

•about 960 000 in the 1970s

•about 1.1 million in the 1980s

•over 900 000 in the 1990s

•over 1.2 million between 2000 and 2010.

The highest number of settlers to arrive in any one year since World War II was 185 099 in 1969–70. The lowest number in any one year was 52 752 in 1975–76.

Immigration as a percentage of Australia's population has been increasing since the late 1990s, after declining rapidly from the late 1960s.

The Humanitarian Program and Asylum-Seekers

In recent times asylum-seeking potential migrants have been the most newsworthy section of the migration process. According to the

United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in 2011 4.3 million people were displaced with a full 800,000 of these fleeing their countries and becoming refugees. The others were therefore internally displaced.

For the world, at the end of 2011 42.5 million people were either refugees (15.2 million), internally displaced (26.4 million), or seeking asylum (895,000). This was a slight decrease on 2010 figures.

The biggest 'producers' of refugees were Afghanistan with 2.7 million, Iraq with 1.4 million, Somalia with 1.1 million, Sudan with 500,000, and Democratic Republic of the Congo with 491,000.

The largest hosting countries were Pakistan with 1.7 million, Iran with 886,500, and the Syrian Arab Republic with 775,400).

Most (80 per cent) refugees were hosted in developing countries.

According to the UNHCR, the figures for Australia were stable with 23,434 refugees and 5,242 asylum-seekers hosted at the end of 2011.

According to

DIAC, in 2010-11 the Humanitarian Program was "fully delivered" with 13,799 visas granted. This was comprised of

5998 Refugee category visas, including: 759 Woman at Risk visas (12.7 per cent of total refugee visas granted)

7801 Other Humanitarian visas, including: 2973 offshore Special Humanitarian Program (SHP) visas [and] 4828 onshore visas.

According to

DIAC, the Humanitarian Program is divided into two: the

onshore protection/asylum component, which "fulfils Australia's international obligations by offering protection to people already in Australia who are found to be refugees according to the Refugees Convention" and an

offshore resettlement component, which "expresses Australia's commitment to refugee protection by going beyond these obligations and offering resettlement to people overseas for whom this is the most appropriate option."

The current debate in Australia is increasingly framed in terms of the disadvantage faced by those offshore refugees compared to those able to get onshore via "irregular" (called 'unlawful' entry) or conventional entry (by visa).

There are two categories of visas for the offshore component of the humanitarian program. These are:

Refugee—for people who are subject to persecution in their home country, who are typically outside their home country, and are in need of resettlement. The majority of applicants who are considered under this category are identified and referred by UNHCR to Australia for resettlement. The Refugee category includes the Refugee, In-country Special Humanitarian, Emergency Rescue and Woman at Risk visa subclasses.

Special Humanitarian Program (SHP)—for people outside their home country who are subject to substantial discrimination amounting to gross violation of human rights in their home country, and immediate family of persons who have been granted protection in Australia. Applications for entry under the SHP must be supported by a proposer who is an Australian citizen, permanent resident or eligible New Zealand citizen, or an organisation that is based in Australia.

The majority of visas granted are derived from offshore. In 2010-11 65 per cent of visas granted were from offshore.

In 2010-11, the biggest source of offshore visa grants went to those from Iraq, with a focus on Africa, the Middle East (Including South West Asia) and Asia.

Aboriginal Australia

What is clear form these statistics is that we're overwhelmingly a nation of relatively recent migrants. But what about Australia's original inhabitants? Any assertion that Australia is a nation of migrants needs not to ignore those of aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin.

According to the 2011 Census:

there were 548,370 people identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin and counted in the Census.

Of these people, 90% were of Aboriginal origin only, 6% were of Torres Strait Islander origin only and 4% identified as being of both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin. These proportions have changed very little in the last ten year period.

In the Northern Territory, just under 27% of the population identified and were counted as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin in the 2011 Census. In all other jurisdictions, 4% or less of the population were of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. Victoria has the lowest proportion at 0.7% of the state total.

Conclusion

Today's asylum-seekers are often pilloried as economic migrants, but most of Australia's population are either recent economic migrants or descended from them. As has been the case throughout modern Australian history, many of those already in Australia worry that new arrivals will make Australia a less attractive place to live. While the rate of immigration should be debated by Australians, it's important that we start from a knowledge of the basic facts. We are a nation of economic migrants.

%2520of%2520gallery14aug12--736x505.jpg)