I've long argued that private debt is a major problem for Australia and could be an even bigger concern if unemployment were to rise in 2016. There are two major ways that debt burdens could become a problem in 2016-17. Firstly, if unemployment rises and secondly, if interest rates rise. It's possible that if unemployment rises then the RBA will cut rates further, but interest payments may not be possible at all if you lose your job and have committed to a loan that is too big to handle. If this happens to enough people with loans then the rate of defaults will rise, but more importantly, the number of forced sales will increase leading to further falls in house prices and an end to the wealth effect that has helped Australians keep spending despite increased indebtedness and uncertainty.

The problem with these predictions is the relevant time frame. As Rudiger Dornbusch once said "The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought". Australia has thus far avoided a negative self-reinforcing spiral where higher unemployment leads to debt defaults, housing price falls and then higher unemployment and so on. Trying to avoid such cycles is the major reason why the Rudd government decided to fiscally support the economy during 2008 and 2009.

Leith van Onselon has written a great article over at MacroBusiness "Aussie Households Bombed on Debt". His article was based on a NATSEM report Buy Now, Pay Later: Household Debt in Australia.

The report reveals:

Foreign debt is also high and the major contributor has been the banks increasing their call on overseas funds.

Household liabilities have been increasing at a greater rate than income - a simple function of increasing debt.

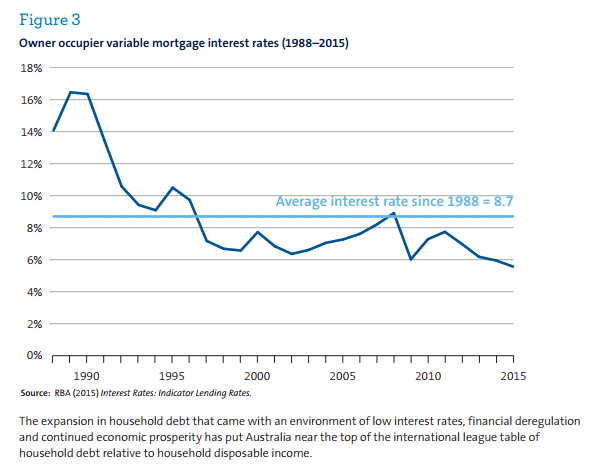

What really matters for households is the ability to service and pay down the debt. Low interest rates have helped enormously in recent years. The fact that the current level of rates is well below the average should be of some concern.

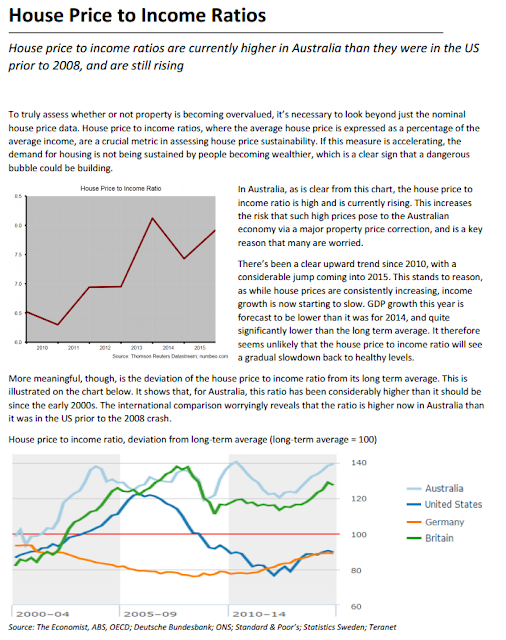

Australian asset holders have largely avoided a fall in housing prices. If prices were to fall, that gap between liabilities and income will seem larger as the assets side of the balance sheet loses value.

However, the really interesting data compares the debt situation for quintiles. This shows that the median ratio has increased for all income quintiles with the low income quintile showing the biggest increase.

Once again, however, low interest rates have made the servicing of debt easier, although the situation has worsened considerably for the lowest quintile.

NATSEM concludes with the following points:

The problem with these predictions is the relevant time frame. As Rudiger Dornbusch once said "The crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought". Australia has thus far avoided a negative self-reinforcing spiral where higher unemployment leads to debt defaults, housing price falls and then higher unemployment and so on. Trying to avoid such cycles is the major reason why the Rudd government decided to fiscally support the economy during 2008 and 2009.

Leith van Onselon has written a great article over at MacroBusiness "Aussie Households Bombed on Debt". His article was based on a NATSEM report Buy Now, Pay Later: Household Debt in Australia.

The report reveals:

“Australian average household debt is now four times what it was 27 years ago, rising from $60,000 to $245,000, reflecting an annual growth rate of 5.3 per cent above inflation and leaving our income growth rate of 1.3 per cent trailing in its wake”

Foreign debt is also high and the major contributor has been the banks increasing their call on overseas funds.

Household liabilities have been increasing at a greater rate than income - a simple function of increasing debt.

What really matters for households is the ability to service and pay down the debt. Low interest rates have helped enormously in recent years. The fact that the current level of rates is well below the average should be of some concern.

Australian asset holders have largely avoided a fall in housing prices. If prices were to fall, that gap between liabilities and income will seem larger as the assets side of the balance sheet loses value.

However, the really interesting data compares the debt situation for quintiles. This shows that the median ratio has increased for all income quintiles with the low income quintile showing the biggest increase.

Once again, however, low interest rates have made the servicing of debt easier, although the situation has worsened considerably for the lowest quintile.

NATSEM concludes with the following points: